New York Once Again Floats Right of Publicity Law

By Jennifer E. RothmanJune 7, 2017

The New York Assembly introduced yet another right of publicity bill last week, Assembly Bill A08155. Such legislation is introduced almost every year in New York―focused on trying to add a post-mortem right which currently does not exist under New York law. Thus far, these bills have all failed to proceed. This time may be different.

The stars are aligning for passage of some bill―even if it hopefully is not this one. One reason for this is that the media companies, that usually strongly oppose such bills, are more willing to compromise this year if the bill provides them with an explicit exemption to avoid liability, particularly in the context of expressive works and news. This sea-change has been brought by a decision earlier this Spring in which a New York appellate court, in Porco v. Lifetime Entertainment, allowed a right of privacy claim to proceed against a television network for its fictionalized drama about a real-life murder. The plaintiff was convicted of having committed the murder, but objected under New York’s privacy statute to the airing of the 2013 Lifetime movie, Romeo Killer: The Christopher Porco Story.

The proposed bill does provide exemptions that should make media companies happy―including an exemption that would protect Lifetime from Porco’s lawsuit. But in the process a lot of other changes to New York’s laws on privacy are included, and very few of them are wise.

Assembly Bill, A08155 turns what used to be a “right of privacy” into a “right of publicity,” that is a freely transferable property right in a person’s “name, likeness, voice, signature or likeness.” The bill appears to eliminate the right of privacy in New York and replace it with a right of publicity. This sea-change is troubling and calls into question the more than 100 years of case law all decided under the privacy statute. The status of privacy itself in New York also would be uncertain if the bill passed.

The created transferability of the proposed right is also problematic. New York’s current law likely does not allow transfers of a person’s identity to a third-party. As I have written in The Inalienable Right of Publicity, allowing such transferability, rather than helping identity-holders, risks their losing control over their own names, likenesses, and voices to creditors, ex-spouses, record producers, managers and even Facebook.

The bill would indeed create the long-awaited post-mortem right of publicity in New York. One that would last for 40 years after death. Such rights can only be enforced under the bill upon registration by the right’s holder. New York does not currently provide any right to control the use of a person’s identity after death. No doubt making those New Yorkers with valuable enough personalities to care about such things jealous of celebrities (or really their heirs) who live in California and receive a 70-year post-mortem right when they die. Approximately 25 states currently offer such post-mortem rights and the number is likely to grow.

But just because some heirs and potential heirs want such a right that does not mean New York should offer one up. What justifies such a right? One need not reward the dead for their lifetime of achievements for which they were already compensated. It is also highly unlikely that the possibility of such post-mortem rights incentivizes the living in any significant (or positive) way. Nor can the dead be offended by bobble-head dolls made in their image.

Sure, loved ones might wish to limit the commercialization of the deceased in the aftermath of her death out of respect, but why should heirs get a 40-year windfall? As the recent battles over Prince’s estate demonstrate the winners of the rights may have little connection to the deceased, or at least none that merits their getting a monopoly in using his identity and reaping hundreds of millions of dollars that could instead be spread more equitably across Prince’s fans and the public.

The post-mortem provision applies to anyone whose identity is used in New York state―most post-mortem rights are limited to those who died domiciled in a particular state. But recently, Washington state and Hawaii have both added post-mortem provisions that apply to those who were not domiciled in the state at the time of death. Such a change in the massive market of New York state will open the floodgates to the heirs of the dead to sue in New York, including those who died in states and even countries, like England, that do not offer such rights to their deceased.

But still there is even more to be concerned about in this proposed bill than the disappearance of the right to privacy in New York and the creation of a post-mortem right that applies to every dead person in the world.

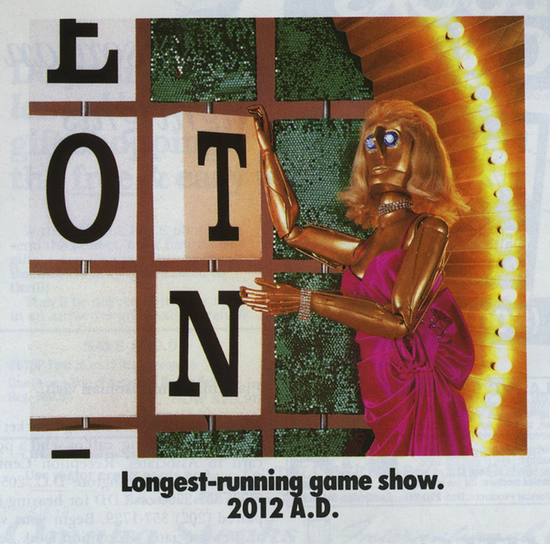

The bill also greatly expands liability for uses of people’s identities. The proposal would expand liability from being limited solely to uses of a person’s “name, portrait, picture or voice” to cover uses of a person’s “likeness,” including uses of any “characteristic” that is “recognizable” of the person, including “gestures” and “mannerisms.” This would be a big change in New York law, which has largely avoided the expansive readings of persona—and liability for the mere evocation of a person—that some other jurisdictions have adopted. The proposed legislation might allow White v. Samsung-like holdings in New York. White allowed liability merely for conjuring up in the minds of viewers Vanna White’s identity by showing a robot on the Wheel of Fortune set wearing a blonde wig and turning letters.

Other changes of note in the proposed bill are the inclusion of a statutory damages provision of $750 per incident. This appropriately protects individuals and has been adopted in some form in a number of states with statutory rights of publicity. This is actually an addition that I support as it equalizes―somewhat―the power of identity-holders who do not have independently commercially valuable identities.

The bill states that it would apply without regard to whether a use is for profit or not for profit, instead of being limited to uses for purposes of trade or advertising. Several enumerated exemptions soften the blow of this otherwise broad reach of the proposed new right. Specific exemptions from liability include uses in “news, public affairs or sports broadcasts,” expressive works, such as plays, books, newspapers, art, radio or television programs, if they are fictional or nonfictional, or if the use is in a work has “political, public interest, or newsworthy value, including a comment, criticism, parody, satire or a transformative creation of a work of authorship.” Advertisements for these items are also exempted. The bill does not define what it means by “transformative creation” and is likely to generate quite a mess of litigation on what is meant by that term―perhaps the bill seeks to import California’s First-Amendment based, transformativeness test. But it is not clear why one would want to import such a confused test that has generated conflicting interpretations and decisions.

Be prepared for something to pass the New York legislature this year or next in light of Porco, and for it to create post-mortem rights in New York. But, let’s hope that what passes is not this bill.

A lot more thought and work needs to go into any proposed right of publicity in New York. In the meantime, just in case, rush out and get your Marilyn Monroe merchandise quickly before she is resurrected from the dead in New York and begins to charge a premium.