50 Cent’s Right of Publicity Claim Preempted by Copyright Law

By Jennifer E. RothmanAugust 21, 2020

Earlier this week, the Second Circuit, in an opinion penned by Judge Pierre Leval, held that a right of publicity claim by rap artist Curtis James Jackson III, better known as 50 Cent, was preempted by federal copyright law.

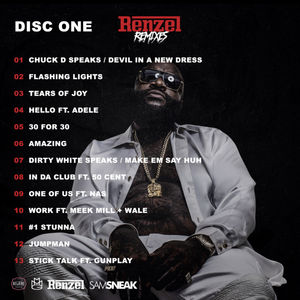

The claim was brought under Connecticut law and arose out of Jackson’s objection to the use of a 30-second sample of his hit song In Da Club and the use of his name. The sample was included in a mixtape Renzel Remixes by another rap artist, William Leonard Roberts II, better known as Rick Ross.

The mixtape was streamed free over the internet with 26 remixes, 11 of which were identified in the track list as featuring the original recording artists whose work was sampled, including Adele, Lil Wayne, and of relevance here—50 cent. The track list appears below:

Jackson sued alleging that the use of his voice in the sample and his stage name on the track list violated his right of publicity under Connecticut common law. Notably, Jackson did not hold the copyright to the work, which was held by the record label Shady/Aftermath.

Roberts did not have permission from either the record label or Jackson to use the sample or his name in the mixtape. The mixtape appears to have been part of a promotional strategy to build demand for a commercial release by Roberts for an upcoming album titled Black Market, but the mixtape was distributed free of charge. The Second Circuit concluded that it was customary in the world of hip hop music to release such mixtapes for free and without getting permission for the samples used.

Roberts moved for summary judgment on three grounds: (1) that the First Amendment protected the use; (2) that the claim was preempted by the Copyright Act; and (3) that Jackson has no publicity rights associated with the song In Da Club because those rights in conjunction with the song were assigned or licensed to Jackson’s record label.

The court quickly disposed of the claim that Jackson had lost his publicity rights, concluding that even if the record label had had a limited exclusive right to Jackson’s name and likeness in conjunction with the song that exclusivity expired prior to the time of the use by Roberts. Jackson therefore could bring a right of publicity claim in relation to the song. The court did not address the First Amendment defense, because it concluded that the copyright preemption defense applied and was an independent basis to toss the claim.

In a lengthy 66-page opinion, the court provided the most extensive analysis of copyright preemption in a right of publicity case that I have seen. It is worth noting that the court did not evaluate whether there could have been a successful copyright infringement claim brought against Roberts by the record label for use of the sample, or a contract-based claim by Jackson against his label for failure to enforce the copyright against Roberts.

Connecticut’s Right of Publicity and Synonymous Appropriation Tort

Before getting into the extensive preemption analysis, it is worth noting that the court concluded that Connecticut would recognize a right of publicity, even though no state court to date has expressly stated this. Connecticut courts have, however, recognized the appropriation tort, and the Second Circuit here concludes that the right of publicity in the state would be synonymous with that tort. So the semantic difference doesn’t have a substantive difference. In part on this basis, the court also concludes that the Connecticut right of publicity applies to noncommercial uses as well as commercial ones. (For more on the role of commerciality in right of publicity cases see Jennifer E. Rothman, Commercial Speech, Commercial Use, and the Intellectual Property Quagmire, 101 Virg. L. Rev. 1929 (2015))

Implied Preemption

The most notable aspect of this decision is the court’s embrace of an approach that I have long advocated for in copyright preemption cases involving the right of publicity―the use of Supremacy Clause preemption or “implied preemption” to determine when “the challenged [state] law stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives” of federal law in the context of copyright law. Op. at 11 (quoting Crosby v. Nat’l Foreign Trade Council, 530 U.S. 363, 373(2000)); see Jennifer E. Rothman, Copyright Preemption and the Right of Publicity, U.C. Davis L. Rev. 199 (2002). In addition to citing to my paper, the court also points to articles by Rebecca Tushnet and Guy Rub, as well as the Nimmer treatise for other recent scholarly support for using implied preemption to navigate these disputes. See Rebecca Tushnet, Raising Walls Against Overlapping Rights: Preemption and the Right of Publicity, 92 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1539 (2017); Guy A. Rub, A Less-Formalistic Copyright Preemption, 24 J. Intell. Prop. L. 327 (2017).

In determining when right of publicity claims conflict with copyright law, the court emphasizes that the conflict must be significant and not “mere[l]y” a “burden [on] the enjoyment of the benefits of copyright.” According to the court, the first step in the implied preemption analysis is to identify the state interests at stake. (I note that this is a similar approach to the one that Robert Post and I advocate in our most recent article on how to analyze First Amendment defenses in right of publicity cases, see Robert C. Post & Jennifer E. Rothman, The First Amendment and the Right(s) of Publicity, 130 Yale L.J. __ (2020) (forthcoming)).

Turning to the Supreme Court’s decision in Bonito Boats v. Thunder Craft Boats, Inc. (1989), involving preemption in patent law, the Second Circuit concludes that state law cannot “render [] fruitless” federal copyright law. Nevertheless, states can regulate various uses of copyrighted works if the regulation does “not conflict with federal policies” underlying copyright law and the state interests at stake are “substantial” and distinct from those behind copyright.

Not every right of publicity claim will meet this standard, but the court suggests that “[m]any right of publicity claims will,” and thus will proceed in spite of the assertion of a copyright preemption defense. The court highlights claims rooted in false endorsement as ones that will usually survive preemption. (I note that outside of Utah, no state right of publicity law turns on likely confusion as to endorsement, but Jackson in his briefs promoted this as his primary interest in bringing the claim). The court suggests that other interests could survive a preemption defense, such as “protecting a person’s privacy, compensating for fraud or defamation, or regulating unauthorized use of its citizens’ persona,” and anti-paparazzi statutes.

In the context of Jackson’s claim, the court concludes that his asserted right of publicity interests are not “sufficiently substantial” in nature. The court concludes that no reasonable person would conclude that he endorsed the use, nor was anything about the use likely to damage his reputation. Accordingly, the court concludes that Jackson’s interest in protecting the use of his identity is minimal, and the “predominant focus” of his claim is objection to the use of the sound recording which Jackson has no right over. His claim is a “thinly disguised effort to exert control over an unauthorized production of a sample of his work.”

Moving to the second step of its analysis, the impact on copyright law, the court concludes that the interference with copyright from Jackson’s claim is “obvious and substantial.” If recording artists and other performers could successfully sue for a right of publicity violation every time a copyrighted performance was used, this would greatly impair the ability of copyright holders and licensees to exploit the work. The court therefore concluded that this was a clear case in which copyright law preempted Jackson’s right of publicity claim.

Section 301 Preemption

The court also embarked on the more common Section 301 preemption analysis while noting its flaws, and preference for the implied preemption approach.

The court concludes that the claim was within the subject matter of copyright (the first 301 inquiry) because Jackson’s voice was captured within a sound recording and the complaint focused on the use of the recording rather than the use of his identity.

The court notes that if there was evidence of a viable false endorsement claim or evidence that there was a particular advantage sought by using and emphasizing the plaintiff’s identity―what the court calls “identity emphasis”―then the claim might not be preempted because then it would not be within the subject matter of copyright.

The court notes that this analysis overlaps with its evaluation of whether the claim is equivalent to a right afforded by copyright law. The court expressly rejects a rote application of the extra element test that some courts have used, and instead considers whether the action itself (rather than the law) is being asserted in a way that makes the claim “qualitatively different from a copyright infringement claim.” (emphasis in original). Here, the court concludes that the claim is equivalent to one brought under copyright because the complaint is about the use of Jackson’s song not his voice. This decision comports with the 9th Circuit’s decision in Laws v. Sony.

Also, of note, the court concludes that the use of Jackson’s stage name (50 Cent) was permissible at least in part because it is a fair use under copyright law to use a person’s name to accurately describe a work.

Ultimately, this case is not likely to spell a dramatic change in the outcome of preemption cases. It very much fits with recent trends, but in terms of its unabashed adoption of an implied preemption analysis it may usher in a sea change in how these cases are analyzed―one that is more coherent, consistent, and logical. As I have described in my book, the outcome of right of publicity cases involving copyright preemption defenses largely track an implied Supremacy Clause-based analysis; they only seem irreconcilable and incoherent if you try to stuff them into Section 301 analysis. Jennifer E. Rothman, The Right of Publicity: Privacy Reimagined for a Public World 161-179 (Harvard Univ. Press 2018). The Second Circuit has thankfully broken us out of that trap.

Jackson v. Roberts, No. 19-480 (2d Cir. Aug. 19, 2020)